02: Spaces

David Michon ponders the potential of a reimagined high street that celebrates shopping IRL

Words by David Michon

If there is one thing we can be certain of, it’s that change is constant. Another thing we can be certain of is how astonishingly wrong we can be about what that change will produce.

The great utopian vision of our time has been centred on the liberating force of Digital. It shall free us from our desks and even our homes; it shall free us from our mundane realities and propel us into virtual ones; it shall finally flatten the world and make anyone and everywhere and everything accessible.

Through this lens, we have written the eulogies of many things – for to achieve this new world, we must destroy the old one. Then, we’ve had to eat those eulogies.

As an example: print. The sheer exhaustion of lugging a book or magazine around – no, thank you. And yes, some publishers are in crisis, and some great magazines have folded – and many a great digital publication has emerged. But so too have some of the most interesting additions to print for a generation; in the magazine world we could name The Gentlewoman, Monocle or Kinfolk. We still pay for pages.

Another example: bricks & mortar retail. Dead, we said – absolutely everything will be bought online. Yes, there’s hardly a day when the modern office receptionist isn’t receiving deliveries from Amazon, or sending them back. But so too have we gained some of the most exciting and gratifying retail spaces our cities have know for a century: T-Site in Tokyo, 19 James Street in Brisbane, or The Commons in Bangkok.

One such space is here, at King’s Cross – a Victorian era coal drops transformed by architect Thomas Heatherwick into a shopping mall-cum-town square: Coal Drops Yard. The architecture is refreshingly sensitive; there’s a streetscape without slipping into high street pastiche; and, the scale is intimate and human.

"The architecture is refreshingly sensitive; there's a streetscape without slipping into high street pastiche; and the scale is intimate and human."

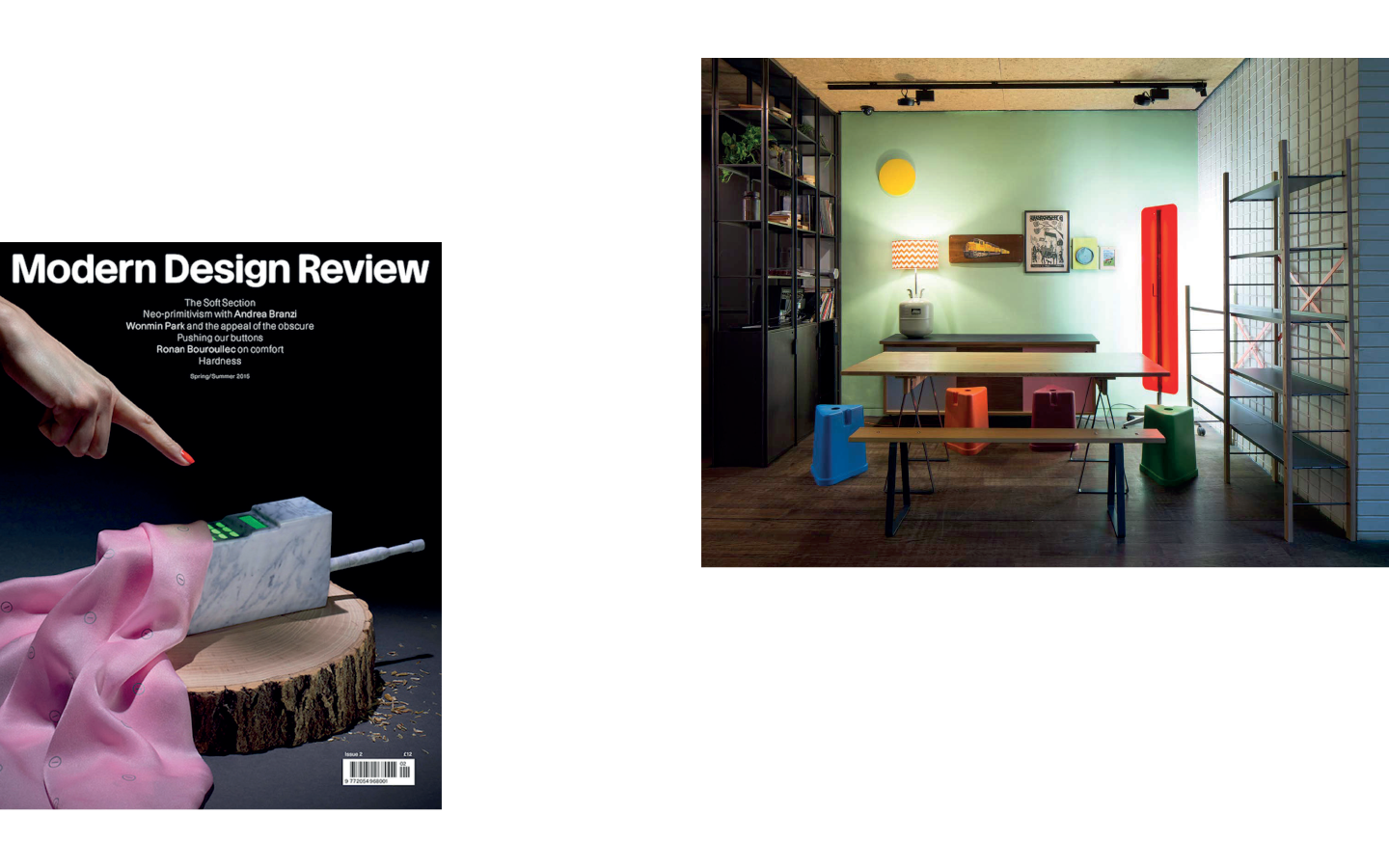

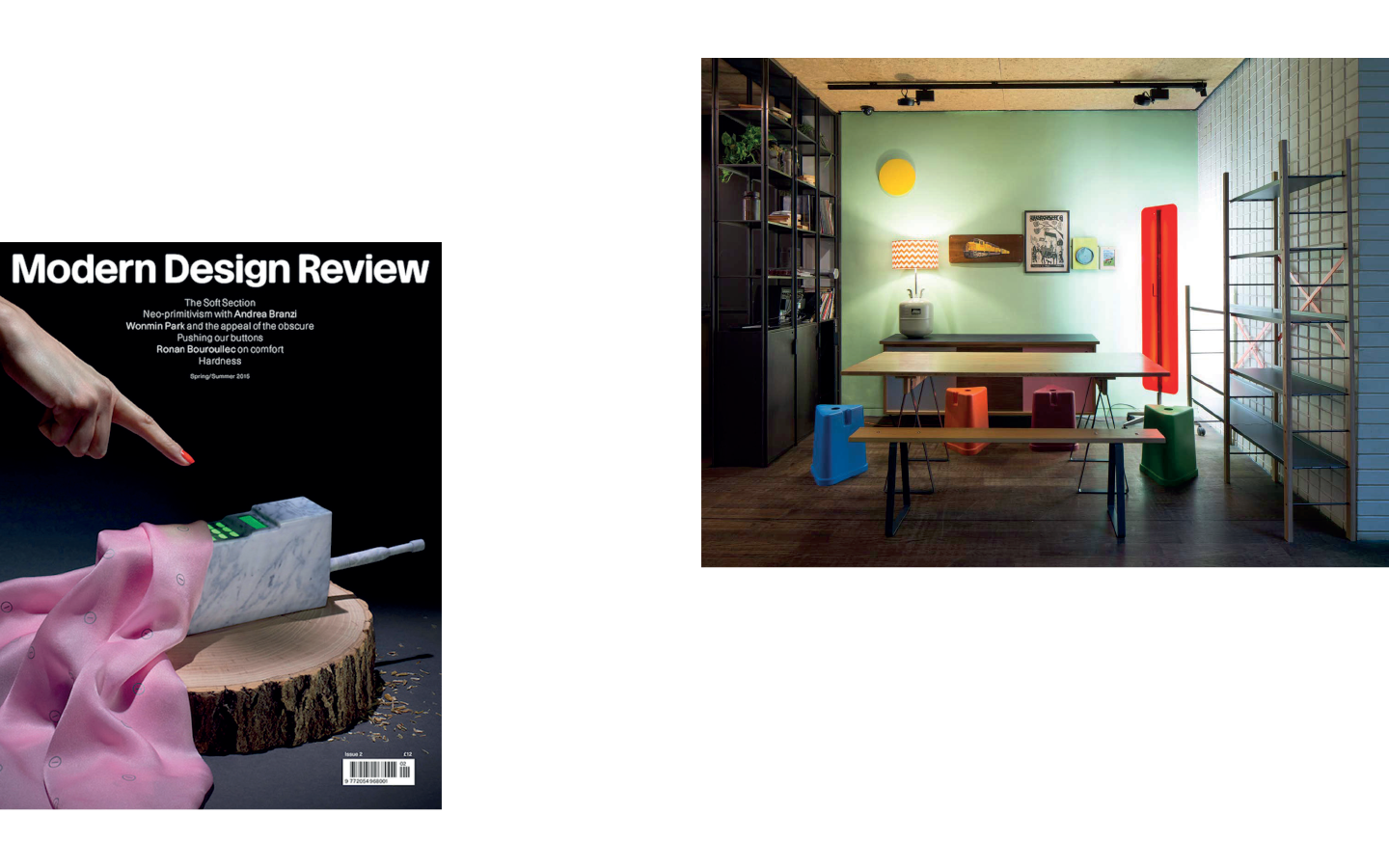

It’s here that we also find Lower Stable Street, and one of London’s more interesting selections of independent shops. And, in fact, two new tenants are – get this – magazines. In the mix are this very magazine, Kiosk, and the Modern Design Review, lifting their presence into permanent 3D spaces.

One might think some grand vision is at work: reclaiming the analogue? Damn the screens? Not quite.

For Laura Houseley, the founder and editor of the Modern Design Review, there’s no underlying revolutionary mission – this is just a step that has come naturally. “I don’t set out to do these things aiming to break down some preconception,†she laughs, “The idea was always to have a physical space – that the magazine would be tucked away at the back of a gallery somewhere.†Design is so much about physicality, and, more and more, Houseley has taken steps to exhibit and sell works that she would usually just write about.

“When I envisaged an MDR gallery, it wasn’t really in such a busy location – and so the concept has had to react to this opportunity,†she explains. The small size of the gallery, just 200 sq ft (the same size as all but one of the shops on the street), means she’s treating it as a vitrine – a display case to draw attention to contemporary design, benefiting from a healthy footfall (potentially up to 50,000 a month). But, it has meant smaller items, easily carried away, have found a place: “It would be foolish not to,†Houseley adds.

In London, with its plethora of rich retail environments – such as a Lamb’s Conduit or Redchurch streets – what would make a small brand plant their stake at King’s Cross – an untested environment for small-scale, independent, maker-driven retail?

Often in these circumstances, it’s about one’s neighbours. When a pocket of retail can become somewhat of commercial and social ecosystem, there’s a much greater chance they will find their audience and flourish. Here, on Lower Stable Street, those include: a bar and off-licence, Can Store, who specialise in working with artists and designers; legendary record shop and label Honest Jon’s; and the East Dulwich- and Deptford-based graphic design studio and shop, iyouall. “It’s not just about footfall,†says iyouall’s Matt Cottis, “but for the sort of brands that are moving in around there, and the places to eat and drink.â€

iyouall photographed by Taran Wilkhu

All share a philosophy, despite their breadth of wares: “It’s about a personal touch,†says Matt Cottis. Of being in the shop, he says “you spend so much time chatting with people… that’s the experience you’d never get online.†And where e-commerce, thriving as it is, often centres on discount, it hasn’t stripped the value of bricks & mortar, but only changed it.

They street is not all about transaction, however. Another of its tenants will be STORE Projects, a community interest company working in art and design workshops for young people – until now entirely a “nomadic association,†operating throughout London but also, last year, Warsaw and Athens.

Their impact on the culture of Stable Street will no doubt be critical: as ideas about consumerism shift, we value experience more and more, and objects less. In many respects, bricks & mortar takes it most of the way: a stroll down the street, small talk with a shop clerk. STORE, however, is hands-on. “Shopping†isn’t just shopping anymore; sometimes, it’s making.

In many ways, the advent of online shopping (and the extreme efficiency of shipping, at least to major cities) has had a positive effect. Basic items can be ordered to you, and when you choose to step out into the world of real-life retail, it’s with a mind to engage, interact and discover.

At risk are the numbingly generic high streets, not so much the passionate and experience-focused smaller sellers, those that have found rich ways to build an audience. Perhaps that is why magazines, with a readership used to seeking a depth of narrative, have laid the perfect groundwork.