02: Spaces

King's Cross Nights

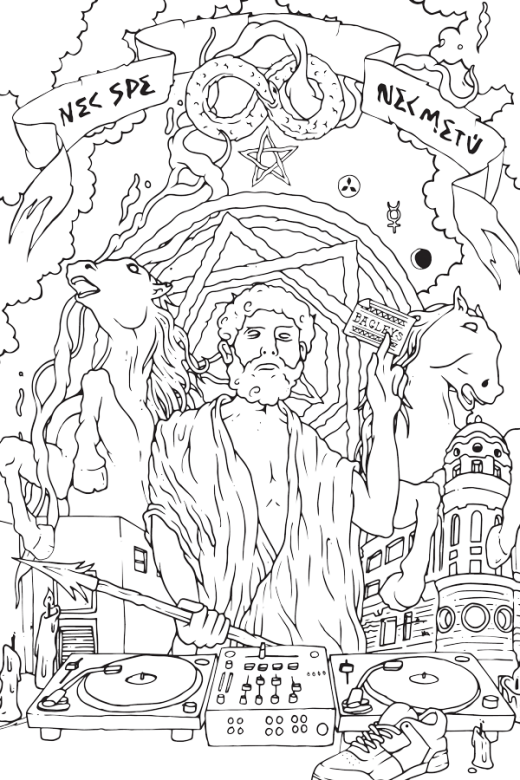

Joe Muggs takes us on an esoteric trip around past and present King's Cross nightlife.

Words by Joe Muggs

Illustration by Jason Kerley

King’s Cross is an area rich with strange and occult histories. Well, of course it is: it's part of London. But even by the psychogeographic standards of the capital, its resonances go far back and deep down, to before it was even part of London. Way back, when there was only the Roman Londinium – what we now call The City – the spot in the countryside up to the north on the river Fleet was the site of one of the first Christian churches in the British Isles.

Indeed, the radical poet and performer Aidan Dunn, who has taken a special interest in the area over the last quarter-century, suggests that St Pancras Old Church may have been the first church in the western hemisphere. Dunn claims this as part of a mystical heritage for the area going back to pre-Christian times, and quotes the visionary artist William Blake's description of the area: “The fields from Islington to Marybone / to Primrose Hill and St John’s Wood / were builded over with pillars of gold / and there Jerusalem’s pillars stoodâ€. The equally wild-minded poet Arthur Rimbaud spent his “year of wonders†in King’s Cross in 1873, writing his most famous works there, and calling it “the miraculous valley of artâ€.

You don't need to be a mystic, or a historian of the fantastical, to know that manic inspiration has continued in the King’s Cross area right through the modern age. Since London became the metropolis we know today with the arrival of the railway age in the 19th century, King’s Cross has occupied a unique position – neither quite central nor peripheral, and like all transport hubs, a place for the transient commerce of the not-quite-rooted. Anyone who, in the late 20th century, came out of the station onto the street, will know that the drug trade and prostitution were its most visible raisons d’etre, but of course – as pre-eminent club historian Bill Brewster puts it, “It always had that seedy edge to it – and clubs and seediness are good matches. They go together.â€

Brewster remembers King’s Cross as part of clubbing history before there were even any club nights there, thanks to the legendary Scala cinema. “In the seventies there were no reliable all-night bus services, so if we’d gone out in London, we'd finish up at Scala. They used to charge £2 or £3.50 for the all-night movies on a Friday and Saturday. They’d show stuff like five Russ Meyer movies back to back and we’d watch the first few and then fall asleep until the first tube came around 5.30-6am. Back then, King’s Cross was a proper dump, very seedy, hookers on the street, with a slightly Satanic feel to it... it did have [radical hangout] Hausman's bookstore, though, and, later, [record store] Mole Jazz.â€

Clubbing proper in the area began with the Battlebridge parties that Irish emigres Noel and Maurice Watson and the late Rip, Rig & Panic bassist Sean Oliver put on in a squatted old school hall in the early eighties – essentially kickstarting the capital’s warehouse party scene. “They were amazing,†says Noel; “Camouflage netting on everything, windows blacked out, members of The Clash, Pistols, Massive Attack there, McLaren bringing down test pressings of Buffalo Girls etc, Neneh Cherry doing the bar. We brought in our first Technics 1200’s and tried to emulate what was happening in NY with the DJs creating mixes from old rare records. Rammed every night until the police shut us down!â€

DJ culture got going in earnest towards the end of the eighties and the industrial area to the north of the station became warehouse party central. Brewster recalls parties in the warehouse space that would become Bagleys: “themed like gameshows, so this one had a car in the middle of the dancefloor, tied up in a massive ribbon. Each time a new DJ came on, a man dressed in a dinner suit and white gloves, walked on to the stage and added the DJ’s name to a big board and removed the last one. Everyone was dancing on top of the car, while inside, a couple were shagging. The second time they did one there, it got busted about 12.30am, just as the drugs were kicking in...â€

"You don't need to be a mystic, or a historian of the fantastical, to know that manic inspiration has continued in the King's Cross area right through the modern age."

Inevitably this led on to legit venues, with first Bagleys, then the adjoining Cross opening to thousands of ravers. One clubber of the time remembers The Cross thus: “There was a massive space and a really good PA. I don't remember a lot – this was the days when everyone would do pills even just for a night down the pub – but I remember that bit. They played lots of Indie and dance tracks and there would be a few thousand people there totally off their nuts. Any and every drug was available and eagerly ingested, and every hour or so, there would be strippers – quite a novelty outside of the few pubs in Shoreditch, at that time.†DJ Andy Blake fondly remembers Bagleys “with the roof full of drug-nuts – no fence around it of course – and the big-name promoter sitting there with carrier bags full of twenties.†It's no coincidence that Bagleys was picked out as the archetypal die-hard nutter rave venue for High Rankin's perennially viral rave advert spoof ‘Raveageddon’ (“56,000 DJs, half a million MC's, MC Det on a bouncy castle!â€).

By the end of the nineties, though club culture in general was fracturing and fragmenting, that of King’s Cross was still thriving. The Scala reopened as a club and gig venue; DJ Jeffrey Disastronaut remembers “five years of unhinged party madness starting in 1999 thanks to evil genius Sean McCluskey and his Sonic Mook Experiment nights at Scala. I started my first set there mixing jungle and death metal, and that set the tone – it was always possible to go from a nice house 1-2 step bounce into to a moshpit. Scala also became the second home of the unjustly-forgotten Asian Underground movement with Tavin Singh, Asian Dub Foundation and Joi playing some memorable shows there.â€

Meanwhile house was still thriving; Bill Brewster and friends ran their Faith sessions “for the older, acid house veteran lot†at The Key, then The Egg when it opened up on an industrial estate up the road in 2003, and Brewster also remembers “great parties at The Cross run by Italians and just full of Italians in dark glasses.†The Egg founded by Trade legend Laurence Malice became a low-key mainstay of London's nighttime landscape and remains so today; the location, says promotions director Hans Hess, “meant that there weren’t many neighbours in the vicinity of the club so it was an ideal location for an indoor/outdoor club†(handy when the smoking ban came in).

Through all of this, the surrounds remained seedy to say the least – conducive, as Brewster says, to the nefarious excitement of clubbing, but with a very dark side too. But then the 21st century waves of regeneration that have surged through London broke hard on King’s Cross, with the regeneration of the station and its goods yard shutting down Bagleys, The Cross and The Key, and driving much of the pimping and heroin trade out too. Jeffrey Disastronaut for one misses the old grit, though: “It's a sterile desert of commodified beige! When it was falling down, feral and abandoned a much richer nightlife culture existed than now.â€

The Egg's Hans Hess puts it pragmatically: “Gentrification generally means that monied people move into the area and therefore the vagabond spirit will of course be affected. Progress is quick and with companies like Google moving their HQ here, I believe that in 5 years the area will be unrecognisable to what it is today.†But something new is filling the space. Nick Keynes, one of the team behind the Tileyard development, which has opened dozens of studio spaces for artists and musicians in the north of King’s Cross, insists that a new creative spirit is in place. “We provide space cheaply to creative people,†he says, “and there are hundreds of those people now working in the area, and more and more restaurants and bars where people meet and get inspiration from each other.â€

It's a long way from throwing up camo nets around an old school hall and partying until the police come. But as with all London's cultural shifts, nothing is forever, and the past never really goes away. The Egg and Scala are still thriving venues, and though throwing a party is no longer the risky game it was, the streets are far from totally sterile at night. And Granary Square – a privately-owned space at the heart of King’s Cross's regeneration programme – was launched with a performance from Aidan Dunn, and a recitation of the area's mystical past. King’s Cross will never be what it was in the time of Bagleys' opening, let alone in the time of Rimbaud or Blake – but can its “vagabond spirit†adapt to the money flooding through it now? History has a habit of never quite disappearing.